Appelez-nous ou envoyez-nous un message WhatsApp: +91 6304795901 ou envoyez-nous un e-mail à l'adresse contact@wanderwise.me

THE HINDU TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE

For those seeking a transformative spiritual journey, the Arunachalesvara Temple in Tiruvannamalai offers an experience steeped in ancient traditions, mystical legends, and profound serenity.

5/21/202524 min temps de lecture

Reading this blog

The fascinating world of Hindu temple architecture opens up an entirely unique and a new realm of its own. Knowing a bit about temple architecture, especially in Tamil Nadu where temples are central to culture and identity, adds rich layers of meaning to your experience—whether you're a visitor, a writer, or a devotee. Even a little knowledge offers a degree of architectural literacy that enriches your understanding and experience.

You stop seeing—you start reading, you appreciate the genius of the builders, it deepens your spiritual experience, you learn history without a textbook, you avoid missteps and misinterpretations & it is just plain fun.

However, there's absolutely no need to burden yourself with all this information—temples can still be enjoyed, appreciated, and understood with just the brief explanations offered by a local guide on the spot.

This blog is filled with Sanskrit and Tamil terms, but I’ve provided English equivalents in brackets and kept the tone clear, succinct and accessible to make it an easy and enjoyable read – and have aided along with photos wherever possible for better understanding.

For foreign students studying architecture, this blog may serve as an eye-opener to the intricate and symbolic world of temple architecture.

For others who might say, “Hey…, well, I think I’ll pass on this,” but would rather like visiting the temples—that’s perfectly understandable too.

So, for those eager to dive deeper—let’s get started! Welcome to the world of Temple Literacy!

Now, let us turn our attention to the architectural elements of the temple itself. Shall we?

The Gopuram – the temple's version of a skyscraper mixed with a fashionista — tall, dramatic, and dressed to impress in intricate carvings and vibrant colours. Painted it looks like by enthusiastic gods armed with a giant box of crayons.

Sometimes you find the minimalistic cousin in half-white; painted half-white usually because there aren’t many sculptures on them.

Both styles are valid, beautiful, and deeply rooted in the temple’s story and tradition. O0ne screams drama, the other whispers legacy.

The various architectural elements of a gopuram

The gopuram—the monumental gateway tower of a Dravidian temple—is one of the most striking and defining features of Tamil temple architecture. While it began as a simple entrance, over centuries it evolved into a lofty, ornate, and symbolic skyscraper of devotion, especially during the Chola, Pandya, and Nayak periods.

Here's a breakdown of the major architectural elements of a typical Tamil gopuram:

Adhisthānam (Base or Plinth): The solid stone platform on which the gopuram stands. Decorated with mouldings and often carved with mythological friezes, yalis, and decorative bands but the main idea is to provide structural strength and elevate the tower.

Bhitti (Wall Portion): The vertical walls above the base, often in stone or brick. They usually contain pilasters, niches, and relief sculptures of deities, guardians, or scenes from epics. They may include entrance passageways, often large enough for processions.

Tāla or Storeys (Stepped Tiers): Gopurams are typically built in multiple tiers (called talas)—sometimes 3, 5, 7, or even 13. Each tier recedes slightly as it ascends, creating the pyramid shape. They are often decorated with stucco sculptures of gods, goddesses, demons, mythical beasts, and celestial beings. No discrimination in temples—everyone gets a spot…eh?!

Kūṭus and Salas (Roof Motifs): Each tier ends with roof forms like Kūṭus, śālas, and nāsikas, which are miniature shrines or vaulted motifs. These are not just decorative—they echo the architecture of small shrines and often contain deities.

Prastāra (Entablature): The transitional space between each tier, often with mouldings, cornices, and small pillars. It may be highly ornate and forms the base for the tier above.

Kalasam (Finial): The very top of the gopuram is crowned with a Kalasam—a bulbous, vase-like finial, usually in metal or stone. The Kalasam symbolizes auspiciousness, fertility, and completion. Sometimes multiple kalashams are used, especially in large gopurams.

Note: The number of Kalashams and the number of pavilions in gopurams are always in odd numbers (1,3,5,7 or 13). It is a reflection of the fact that truth, god & the universe is one. They are non-dichotomous & indivisible.

In Vedantic philosophy, especially Advaita (the philosophy of oneness), Brahman is the ultimate reality—formless, infinite, and indivisible. The universe is a manifestation of Brahman, and truth (Satya) is the expression or realization of that oneness.

Truth (Satya), God (Brahman), and the Universe (Jagat) are seen as one.

Dvārapālas (Guardian Figures): Flanking the entry passage are giant, fierce guardian deities, usually two in number. Their purpose is to protect the temple precinct and ward off evil influences.

Torana (Arch or Decorative Frame): Above the entrance, you'll often find a Torana—an ornate arch with floral, geometric, or narrative carvings. The Torana acts as a visual transition into the sacred world beyond.

Stucco Work: Particularly from the Nayak period onward, stucco figures (plaster over brick or stone) became prominent. These depict mythological stories, avatars, and divine processions, making the gopuram a vertical narrative wall.

Bonus: Colour and Iconography: In Tamil Nadu, gopurams are often vibrantly painted, especially in temples like Madurai Meenakshi or Srirangam. The colouring emphasizes storytelling, making the tower both an architectural marvel and a theological textbook.

In traditional Hindu practice, whenever a house was constructed or a temple consecrated, a cow was ceremoniously led into the space to sanctify it. The term gopuram—often interpreted as the temple’s grand entrance—derives from “go” meaning cow, symbolizing this sacred ritual. It signifies the entrance through which the revered cow was ushered in to bless the premises. By the same token, the name Goa is sometimes poetically interpreted as the “land of cows.”

Introduction

Before you dive headfirst into the glorious labyrinth of Hindu temples — all those towering gopurams, echoing halls, and mysterious corridors — it helps to know a few architectural elements. Trust me, once you know what a Vimana or a Mandapa is, everything starts making sense (and you stop calling every pillar “that cool carved thing”).

But hey — if you’re the type who likes to let one stone lead to the next, one page unfold at a time, and you believe that mystery is part of the magic... feel free to skip this blog. Just wander, wonder, and let the temple reveal itself to you.

For the rest of us, curious cats — let’s decode the divine blueprint, one sacred stone at a time.

For this blog, I’m focusing exclusively on the Dravidian-style temples of Tamil Nadu. While the South Indian temple architecture is broadly known as the Dravidian style, its northern counterpart is the Nagara style. In Central India—where these two cultural zones converge—a hybrid form called the Vesara style emerged, blending features from both traditions.

Temples in other southern states like Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka largely follow the Dravidian template, with regional variations in detail and execution. However, the temples of Kerala, though similar in basic layout, differ markedly in their materials, construction techniques, and especially their front elevation. These warrant a separate discussion of their own.

Dravidian Hindu temple architecture is stunningly intricate—so much so that if you're a first-timer without a decent guide, you're basically just nodding at centuries of genius, pretending you get it. It’s like being handed a beautiful book in a language you can’t read—gorgeous, yes, but also frustrating.

Let me briefly break it down the key elements for you (common for all the temples with minor differences) —minimum scholarly jargon, no architectural thesis, I promise. Just enough so you can look at the place and go, “Ah, now that makes sense!” instead of “Is that a pillar... or a really fancy drainpipe?”…..

The Sacred text called the Vāstu Śāstra

Vāstu Śāstra, the ancient Indian science of architecture, offers detailed and sacred guidelines for temple construction. In the context of temple building, especially in the Dravidian tradition, Vāstu Śāstra treats the temple not just as a physical structure, but as a living embodiment of cosmic principles.

Here’s what it emphasizes:

Temple as a Cosmic Diagram: (Vāstu Purusha Mandala): At the heart of Vāstu Śāstra is the Vāstu Purusha Mandala, a sacred geometric grid that represents the cosmic man (Purusha) lying face down. The layout of the temple—its orientation, dimensions, and proportions—is derived from this grid. The sanctum (Garbhagriha) is placed at the Brahmasthana, the central and most powerful point, like the head or soul of the structure.

Orientation & Placement: Temples are ideally aligned along the east–west axis, with the main deity facing east to greet the rising sun—symbolic of spiritual awakening. Surrounding structures like mandapams, gopurams, and prakaram are placed with precise orientation to maintain energetic balance.

Proportions and Measurements (Māna): Every element of the temple—from the height of the vimana to the width of the steps—is calculated using canonical proportions, often based on the taalam (unit of measurement derived from the human body). Even sculptures and icons must adhere to specific proportions laid out in the Śilpa Śāstra, a subset of Vāstu Śāstra.

Materials and Elements: Materials like stone, wood, and metal are chosen not just for strength, but for their symbolic and energetic properties. Certain rituals purify the site and the materials before construction begin, ensuring alignment with natural and divine energies.

Function of the Temple: The temple is not merely a place of worship, but a microcosmic replica of the universe, a spiritual engine where divine energy is concentrated and made accessible to humans. The journey from the entrance (symbolic of the outer world) to the sanctum (the inner self) is a symbolic spiritual journey.

To summarize, Vāstu Śāstra treats temple architecture as a sacred science, aiming to harmonize space, energy, and divinity. It’s where metaphysics meets geometry, and ritual meets structure.

The Sacred text called the Agamas

The Āgamas—sacred scriptures central to many South Indian Hindu traditions—play a foundational role in temple architecture, especially in the Dravidian tradition. While Vāstu Śāstra provides the architectural framework and measurements, the Āgamas focus on the spiritual, ritualistic, and symbolic dimensions of temple construction, consecration, and worship.

Here’s what the Āgamic texts say about temple architecture:

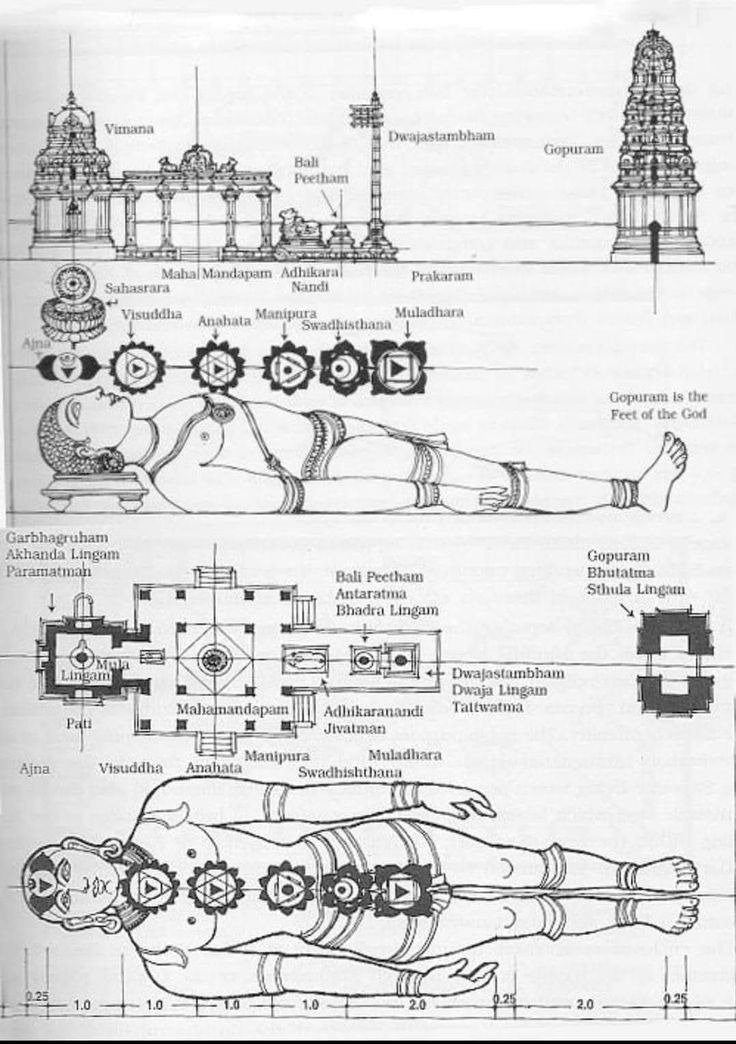

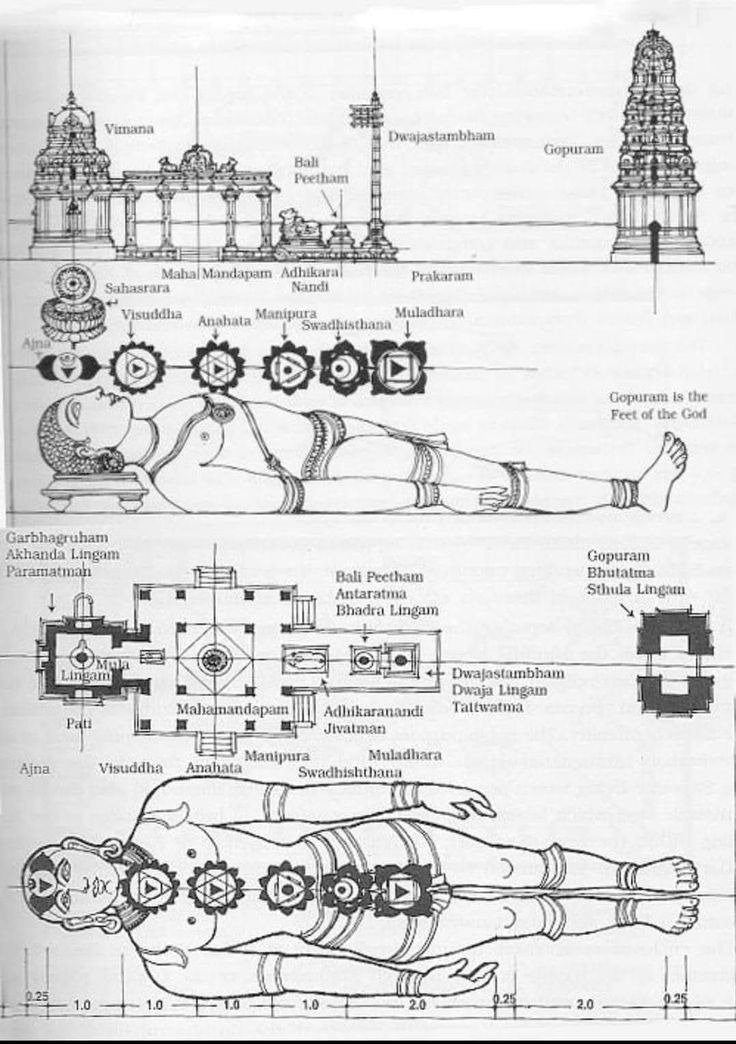

Temple as a Divine Body: Āgamas describe the temple as the body of the deity—not metaphorically, but as a manifested form of the divine. Each part of the temple corresponds to a specific body part of the deity (e.g., sanctum as the head, mandapam as the body, and gopuram as the feet). This reinforces the idea that entering the temple is entering the divine presence itself.

Strict Prescriptions for Every Element: The Āgamas provide detailed guidelines for: Site selection and purification, Iconography: How deities should be sculpted, their gestures (mudras), expressions, and proportions, Temple layout: Placement of shrines, mandapams, tanks, gopurams, flag staffs (Dwaja Sthambam), etc. & Orientation: Main deities typically face east unless prescribed otherwise (e.g., Shiva in some temples faces west)

Types of Temples: Āgamas classify temples into different types based on: The presiding deity (Shaiva, Vaishnava, Shakta, etc.), the purpose (daily worship, festivals, pilgrimage, etc.), the size and complexity, often with poetic names like Meru, Kailasa, Chaturmukha, etc., each with unique architectural forms.

Ritual Integration: The temple is not complete without its rituals. The Āgamas prescribe: Prāṇa-pratiṣṭhā: Ritual to infuse life into the deity, Daily worship (Puja), festivals, and temple processions, maintenance of temple purity, including who may enter certain spaces and when.

Temple as a Yajñaśālā (sacrificial space): The entire temple is seen as a cosmic altar where worship and rituals are offerings to the divine. This connects temple architecture directly to Vedic sacrifice, but in a more symbolic and permanent form.

Types of Agamic Schools: Shaiva Āgamas (used in most Tamil Shiva temples), Vaikhanasa and Pancharatra Āgamas (used in Vaishnava temples like Tirupati), Shakta Āgamas or Tantras (used in Devi temples)

The temple layout like a human body

Dravidian temple layouts—especially in South Indian temple architecture—are often designed to mirror the human body (or cosmic man, known as Purusha) because of deeply rooted symbolic and philosophical principles in Hindu thought. This concept is called the "Vaastu Purusha Mandala", which aligns the microcosm (human) with the macrocosm (universe).

Here’s a breakdown of how the layout relates to the human body:

Head – Garbhagriha (Sanctum Sanctorum): The Garbhagriha, where the main deity resides, is considered the head or brain. It is the most sacred and innermost space, symbolizing consciousness or the soul.

Heart – Antarala (Vestibule): The Antarala connects the sanctum to the rest of the temple, representing the heart, the transition from the divine to the physical world.

Stomach – Mandapam (Pillared Hall): The mandapam is a public hall used for rituals and gatherings. It symbolizes the stomach, where nourishment (spiritual or communal) happens.

Legs – Prakaram (Temple Corridors): The prakaram, or walking path around the sanctum, are like the legs, allowing devotees to circumambulate (Pradakshina), symbolizing movement and action.

Feet – Gopuram (Temple Gateway): The gopuram, or grand entrance tower, is seen as the feet—the point of entry into the spiritual body of the temple.

Philosophical Rationale: The temple is seen as a living being, just like the universe is a living, breathing entity. By entering the temple and walking toward the sanctum (the “head”), the devotee is spiritually ascending from the material (feet) to the divine (head). This journey mimics spiritual evolution and aligns the devotee’s inner journey with the universal order.

The Pallava style

The Pallava style of temple building, which flourished in South India (mainly Tamil Nadu) between the 6th and 9th centuries CE, is significant for being one of the earliest and most influential phases in the development of Dravidian temple architecture.

Rock-cut temples could be built only in places where such huge rocks were available because of natural formation. However, the Pallavas cut blocks and slabs of stone and assembled them to build temples wherever they wanted by building their own structure. The Pallavas pioneered the transition from rock-cut cave temples to free-standing structural temples. The Pallavas established the Dravidian style elements & started fine carving on granite stones.

The Chola style

The Chola style of architecture (9th–13th centuries CE) built upon the foundation laid by the Pallavas, but took temple building to an entirely new level—both in scale and sophistication.

If the Pallava temples were modest in height and size the Chola temples were massive and imposing. While the Pallavas experimented with freestanding temples, the Cholas perfected structural temples using granite blocks laid without mortar. Whilst the Pallava carvings were innovative and narrative-rich the Chola temples feature exquisitely detailed sculptures of deities, celestial beings, and dancers — often stand alone without any narration. A single sculpture would tell a story. Plus the bronze Nataraja, a Chola innovation in metal casting, became iconic.

The Pallava temples had relatively simple layouts: sanctum (Garbhagriha), vestibule, and hall. The Chola temples evolved into complex multi-shrine compounds with axial alignments, massive prakaram (circumambulatory) walls, and expansive mandapams (pillared halls) for rituals and gatherings.

While the Pallava temples were meant for atonement, the Chola temples were not just religious sites—they were centres of administration, education, arts, and economy.

While Pallava gopurams were rudimentary, the Cholas began the trend of elaborate gateway towers—though this feature would be fully expanded by the later Pandya and Nayak dynasties.

The Pandyas’ contribution

Instead of always building from scratch like the Cholas, the Pandyas often expanded earlier temples, especially Chola and Pallava sites, by: Adding new gopurams (gateway towers), Building additional prakaram walls (enclosures) & Adding intricately sculpted mandapams.

Pandyas emphasized delicate ornamentation, particularly in vimanas, pillars, and lintels. Most importantly: The Pandyas contributed to the concept of the temple-centred town, or "Maada Veedhi" system, where streets were laid in concentric squares around the temple, often corresponding to ritual processions.

The Vijaya Nagar’s contribution

The Vijaya Nagar Empire (1336–1646 CE) made several significant contributions to South Indian temple architecture, leaving a lasting legacy that blended earlier traditions with new stylistic innovations. Here are the key contributions:

Revival and Patronage of Temple Building: Vijaya Nagar rulers actively revived Hindu temple construction after earlier disruptions from invasions. They became major patrons of Hindu architecture, encouraging the building and renovation of grand temples across South India.

Dravidian Style Enhancement: They advanced the Dravidian style of architecture, characterized by: Tall, ornate gopurams (gateway towers): Often taller than the main sanctum, richly decorated with sculptures, mandapams (pillared halls): Expanded in size and number, used for gatherings, rituals, and dancing, enclosure walls (prakaram): Temples were enclosed by high walls, giving them a fortress-like appearance.

Distinctive Features Introduced: Kalyana Mandapams: Marriage halls for divine weddings, elaborately carved, Raja gopuram: Monumental entrance towers named after kings (e.g., Krishnadevaraya), reflecting royal patronage, decorative pillars: Iconic pillars featuring rearing horses or mythical creatures trampling enemies, especially in mandapams & elaborate use of granite: Temples used more granite for durability, especially in base structures.

Integration of Art and Sculpture: Extensive use of intricate sculpture and iconography came into play during this period, depicting deities, mythological scenes, court life, and processions. Sculptures often reflected religious themes and worldly grandeur, symbolizing royal power.

Temple Town Planning: Vijaya Nagar rulers developed temple-cantered urban layouts, with temples acting as socio-economic hubs. The capital city, Hampi, itself was a major religious and architectural centre, with iconic temples like the Virupaksha and Vittala temples

The Nayaks’ contribution

The Nayaks were the vassals of Vijaya Nagar dynasty. The Nayak period was marked by extravagance and theatrics. Temples were no longer just sacred—they were spectacles. So, Huge gopurams (gateway towers), bursting with a riot of stucco sculptures in vivid colours, became the visual signature. Temples became like cities, with vast enclosures, multiple shrines, corridors, halls, tanks, and gardens.

Colossal Pillared Mandapams: The Nayaks built some of the largest and most elaborately carved mandapams (pillared halls) in India.

Stucco Overload (In a Good Way): Unlike the stone-heavy Chola style, the Nayak aesthetic favored layered, multicolored stucco sculptures covering the gopurams. Figures of gods, goddesses, demons, animals, and mythological scenes crowd the towers in dense, almost cinematic compositions.

Maze-Like Complexity: Nayak temples were designed for processional drama, with multiple concentric corridors, twisting inner sanctums, and labyrinthine spaces. They introduced long pillared corridors (prakaram mandapams), some stretching hundreds of meters, as in Rameswaram temple.

Living Ritual Theatre: Temples in this period were centres of culture—with music, dance, festivals, and daily rituals performed on a grand scale. The architecture was meant to amplify the experience—processions, light, sound, and movement were all choreographed with the temple as stage.

To help a foreign student grasp the progression of South Indian temple architecture—from Pallava to Chola to Pandya and Vijaya Nagar/Nayak styles—it’s useful to draw a parallel with the evolution of Western architecture: from the sturdy simplicity of Romanesque, to the soaring grandeur of Gothic, the harmonious refinement of the Renaissance, and finally the ornate theatricality of the Baroque.

Vimana (The superstructure above the sanctum sanctorum)

The Vimana is basically the fancy hat the sanctum wears — tall, tiered, and totally extra. It sits right above the sanctum like. “Unlike the Gopuram (the over-the-top extrovert at the gate), the Vimana is more refined — a classy introvert who’s got style but doesn’t shout about it. It's usually pyramid-shaped, and it's not here to compete. It knows it's spiritually superior.

The Vimāna is the tower or spire directly above the Garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) of a temple and is a core feature of Dravidian temple architecture. Unlike the gopuram, which is an ornate gateway, the Vimana is sacred and symbolic, marking the spiritual heart of the temple where the deity resides.

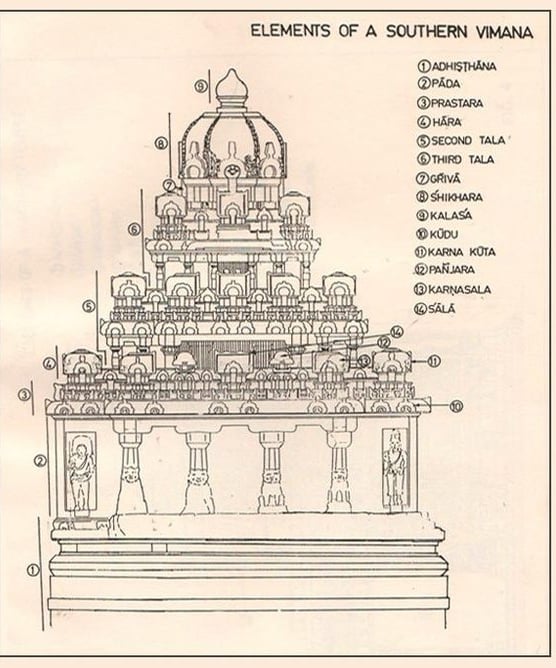

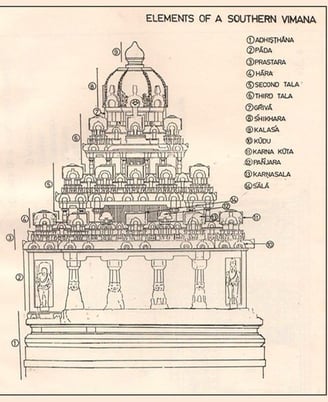

Here are the main architectural elements of a Tamil Dravidian Vimāna:

Adhisthānam (Base or Plinth): The platform on which the Vimana stands. The base typically is composed of several moulded layers (mouldings called jagati, kumuda, pattika, etc.). They are sometimes adorned with narrative friezes or sculpted yalis and lions.

Bhitti (Wall of the Sanctum): The vertical wall of the Garbhagriha. Usually plain or minimally decorated in early temples (like Pallava), but later Chola and Nayak vimānas feature devakulikas (miniature shrines), niches, and pilasters.

Talas (Storeys or Tiers): The Vimana rises in a stepped pyramid form, usually with 3 to 7 diminishing storeys (talas). Each Tala is a progressively smaller layer stacked above the sanctum. In Tamil Nadu, these are solid, not hollow, unlike the gopurams’ higher tiers. Each storey may feature kutas, śālas, and panjaras (miniature shrine motifs).

The Griva (Neck) is the transitional cylindrical or octagonal element between the last Tala and the finial (shikhara). Sometimes features devakulikas or small deity niches facing four directions are added.

Shikhara (Crowning Element): In Dravidian architecture, this is usually not a curvilinear spire (as in Nagara temples), but a solid dome-like structure or stupi. Example: The Sri Vimana in Chola temples, like Brihadeeswarar Temple, has a massive octagonal shikhara. It symbolizes cosmic completeness.

Kalasam (Finial or Sacred Pot): The very top of the Vimana, a metal (often gold-plated) or stone finial shaped like a pot. It symbolizes abundance, divine energy, and fertility.

Antarala (Vestibule / Connector): The small anteroom connecting the Garbhagriha to the ardha-mandapa. Architecturally, it may or may not be visible from outside but forms part of the vimāna complex.

Padabandha or Upapitha (Sub-base): Sometimes a secondary plinth or basement on which the Adhisthānam stands, especially in monumental vimānas. It offers additional visual grounding and support.

To Summarize: A Dravidian Vimana is compact, massive, and sacred—unlike the soaring gopurams, which became taller in the later periods. The Vimana is the axis mundi of the temple, aligning the deity’s presence with the cosmos through form, proportion, and elevation.

Mandapams (Pillared Halls)

The Mandapa is basically the temple’s living room — spacious, social, and full of drama (literally, sometimes there are dances and music performances here).

With its rows of elaborately carved pillars, it’s like a stone fashion runway where every pillar is screaming, "Look at me, I took centuries to get me carved!"

It’s where devotees gather, ceremonies happen, and if the deity were throwing a party — this is where the snacks would be served. You’ve got different types too: one for weddings, one for hanging out, one for rituals... it’s like the temple version of having a drawing room, a dining room, and a party hall — all in sacred stone.

Types of Mandapams

In Dravidian temple architecture, especially in Tamil Nadu, mandapams (pillared halls or pavilions) are integral architectural and ritual spaces. They serve various purposes—from hosting deities during festivals to providing shelter for devotees and rituals. Over centuries, mandapams evolved from simple halls to highly ornate and function-specific structures.

Here are the major types of mandapams commonly found in Tamil temples:

Ardha-mandapam (Half Hall or Vestibule): Located immediately in front of the Garbhagriha, connecting it to the next hall is the transitional space between the sanctum and larger halls. These are usually narrow and enclosed—acts as an antechamber.

Maha-mandapam (Great Hall): The main and largest pillared hall, used for public rituals, devotional gatherings, and festivals. These are usually richly decorated with intricate ceiling and pillar carvings. Sometimes includes a raised platform for dance, music, and recitation of scriptures.

Mukha-maṇḍapam (Front Hall / Porch): The entrance porch or hall leading into the inner parts of the temple. "Mukha" means face—this hall “faces” the temple and invites devotees inward. These may be open or covered and often features Dvārapālas (guardian figures).

Kalyāṇa-maṇḍapam (Marriage Pavilion): A ceremonial hall used for symbolic divine weddings—especially the annual celestial marriage (kalyāṇotsavam) of the presiding deity. These are often richly decorated with sculptures of wedding scenes, musicians, and dancers. They are typically located in the outer prakaram or precinct.

Ranga-maṇḍapam (Stage Hall): Built as a performance space for dance, music, or theatrical enactments, especially during temple festivals. They are usually on a raised platform and spacious layout. Famous examples: the Thousand Pillar Hall in Madurai Meenakshi Temple.

Vasantha-maṇḍapam (Spring Pavilion): Used during the Vasanthotsavam (spring festival), when the deity is ceremoniously brought here. They are often situated in a garden or open area, symbolizing freshness, beauty, and seasonal change.

Unjal-maṇḍapam (Swing Pavilion): Contains a swing (unjal) on which the Utsavam murti (processional deity) is gently rocked during evening rituals. They are seen in temples like Srirangam and Kanchipuram. They symbolize relaxation and divine play.

Nṛtta-maṇḍapam (Dance Pavilion): Specifically designated for classical dance performances, often as offerings to the deity. They may be part of or adjacent to the maha-maṇḍapam. They feature pillars with sculptures of dancers and musicians.

Dolotsava-maṇḍapam (Festival Pavilion): Used for seasonal or daily utsavas, especially when deities are taken out for processions and temporarily housed here. They may be open-sided for ventilation and visibility during events.

Yāgaśālā (Fire Ritual Pavilion): A temporary or permanent structure used for Vedic fire rituals (yāgas). Found especially during Kumbabhishekam (consecration) ceremonies or major temple festival

Dwaja Sthambam (Flagstaff)

The Dwaja Sthambam — the tall, proud pillar standing right in front of the sanctum like a spiritual announcer. It basically used to be the temple’s version of a status update: tall, shiny (usually), and always standing at attention. Traditionally a stump of wood covered in shiny brass (sometimes gold-plated).

In the olden days during festivals, flags are hoisted on it to announce divine events. Now a days it is just an ornamental piece in a Hindu temple but still an important part of the temple.

It is before the flag pole a Hindu devotee prostrates as an act of surrender beyond which he/she has nothing to ask from the gods!

Nandi bull mandapam (Divine Nandi bull pavilion) in a Shiva temple

A typical pillared hall (Mandapam) of a Hindu temple inner corridor

Nandi Mandapa (Bull Pavilion - only in Shiva temples)

This is where the sacred Nandi, Lord Shiva’s loyal ride and ultimate bestie, sits like a stone VIP — right in front of the sanctum, staring at his boss with eternal devotion (zero blink breaks). The Nandi Mandapa is his personal chill zone — a dedicated little pavilion that’s basically the celestial version of “reserved seating.” He doesn’t speak, doesn’t move, but you just know he’s got all the divine gossip. It’s said that if you whisper your prayers into Nandi’s ears, he’ll pass them on to Shiva directly — which makes him part sacred bull, part spiritual courier & part very quiet therapist.

The origins in South India – Mahabalipuram

In the earliest phases of Hindu practice, there were no temples or idols. Worship was centred on the sacred fire (Agni), lit with sandalwood, twigs, and fragrant herbs. Offerings of ghee (clarified butter) were poured into the flames while Sanskrit hymns from the Vedas were chanted in deep reverence. The rising smoke was believed to carry the prayers and offerings to the gods and ancestral spirits, invoking their presence and blessings. It was a ritual of pure sound, fire, and intention, performed in open spaces—an expression of cosmic harmony rather than constructed sanctity.

The Vedic Ritual Tradition: Fire, Hymns, and Offerings: There were no temples, no murti (idols), and no permanent structures. Worship was ritualistic, not devotional—focused on sacrifices (yajña) and chants (mantras). Fire (Agni) was central. Agni, the fire god, was the primary medium through which offerings were sent to other deities.

Priesthood and Precision: Only Brahmins, trained in Vedic recitation and ritual, could perform these ceremonies. Rituals had to be done with precise pronunciation and timing (Siksha), often in open-air altars.

In the post-Vedic developments (~500 BCE onward) with the rise of Bhakti (devotion) and the Puranic deities (like Vishnu, Shiva, Devi), religion became more personal and visual. People wanted places to see and worship deities—thus temples with idols emerged.

In the mean time Buddhism popularized religious monuments and public art. From the 3rd century BCE onward, especially under Ashoka, Buddhism used Stupas (Buddhist temples), monasteries (viharas), and rock-cut chaityas to create sacred spaces accessible to the public. These structures were often visually appealing, symbolically rich, and widely visited. Stupas became spiritual centres that housed relics and attracted pilgrims.

Buddhism used art to teach and attract followers. Reliefs, sculptures, and murals on Stupas and cave walls (like Sanchi, Ajanta & Ellora) told stories from the Jataka tales and Buddha’s life. This made Buddhism visually engaging, narrative-driven, and attractive to people of all classes—not just elites or priests.

Now, the Hindus also wanted to be abreast of what was happening.

Hinduism responded and adapted. As Buddhism spread, Hindu communities began to feel the need for more structured spaces of worship, visible symbols, and accessible rituals. This likely motivated the gradual shift from fire altars to temples, especially as Bhakti (devotion) emerged. In fact, many early Hindu temples borrowed forms and styles from Buddhist models—especially in rock-cut architecture (e.g., Elephanta Caves, Ellora Cave 16 – the Kailasanatha Temple).

Temple building flourished during the Gupta period (4th–6th century CE) in North India. As the Guptas in North India began building structural Hindu temples in brick and stone, the idea of permanent sacred space spread south.

The Pallavas were deeply influenced by Buddhist and Jain rock-cut caves from western India (In places like Ajanta, Ellora, Bhaja & Karla) & Andhra Pradesh (Nagarjunakonda & Guntupalli). These sites featured chaityas, viharas, pillars, and intricate carvings—but were mostly Buddhist or Jain.

The Pallavas adapted the rock-cut medium to craft Hindu shrines of their own. Unlike the Guptas, who favoured brick and wood, the Pallavas daringly chose granite—transforming the region’s hardest stone into enduring sanctuaries of devotion and art.

The Pallavas’ choice of granite over brick and wood—used more commonly by the Guptas in North India—was both practical and symbolic, shaped by regional factors, political vision, and religious purpose. Although no direct inscriptions or texts explicitly state why the Pallavas chose granite over brick or wood, scholars generally conjecture that several factors may have influenced their preference for granite. The following are the possible reasons:

Local Availability of Granite: In the Pallava heartland (around Kanchipuram, Mahabalipuram, and Tiruchirappalli), granite was abundant, while good brick clay and timber were less so, or more perishable. It was natural to work with the hard stone available locally—even though it required greater skill and effort to carve.

Desire for Permanence and Immortality: Granite symbolized eternity. Pallava kings—especially Mahendravarman I and Narasimhavarman I—wanted their religious and political statements to outlive them. By carving shrines from solid rock (monoliths and cave temples), they demonstrated architectural daring, royal power & their devotion - cast in stone.

Technological and Artistic Ambition: The Pallavas had access to skilled sthapathis (temple architects) and artisans capable of granite carving, influenced by: Earlier Buddhist and Jain cave architecture, Rock-cut sites in the Deccan and Andhra Pradesh. Their experimentation gave rise to: Cave temples (e.g., Mandagapattu), Monolithic shrines (e.g., Pancha Rathas – the five chariots) & Structural temples in stone (e.g., Shore Temple)

Religious shift towards Agamic Worship: The rise of Agamic Shaivism and Vaishnavism demanded permanent sanctums and murtis (idols), which stone temples supported better than temporary brick or wooden structures. Granite temples allowed for complex iconography, sacred geometry, and the cosmic symbolism encoded in Agamic temple plans.

Thus was born the monuments at the grand UNESCO site of Mahabalipuram - the place of architectural experiments of granite stone. The story of Mahabalipuram, with its windswept shores and stone-carved marvels, deserves its own spotlight—and will be told in a separate blog post.

Penance panel granite sculpting in Mahabalipuram

The Garuda – Human form of eagle

If Shiva has Nandi — the ultimate chill bull — then Vishnu has Garuda, the mighty eagle-man with serious VIP energy. You’ll spot him perched (well, kneeling actually) right in front of the sanctum in Vishnu temples, in a straight line with the deity, ready to launch into cosmic airspace at any moment. With wings folded, eyes locked on Vishnu, and the posture of someone who’s been doing spiritual squats for centuries, Garuda is the temple’s resident divine air force commander and Vishnu’s number-one ride.

He’s the symbol of speed, strength, and loyalty — basically the Uber Premium of the gods, but with feathers and attitude.

With a respectful nod and a little hi, he’s the one to take your message straight to Vishnu — express delivery, no middlemen.

The divine human-form-of-eagle in a Vishnu temple

Prakaram (Enclosure Corridors)

Imagine a divine racetrack around the sanctum — that’s your Prakaram. These are the pathways or corridors that wrap around the temple, giving devotees a chance to stretch their legs and their spiritual muscles.

There can be one, two, even seven of these concentric enclosures in big temples, like holy onion layers. Walking around them (clockwise, always clockwise!) is called pradakshina, and it's basically cardio with cosmic brownie points.

The inner Prakarams are usually covered, offering shade, cool stone floors, the outer Prakarams, on the other hand, are open to the sky — giving you sun, breeze, and a real-time weather report as you walk.

Navagraha (The Nine Planetary Deities – only in Shiva temples)

Enter the Navagraha — a cosmic board of planetary directors managing everything from your mood swings to your marriage prospects. These nine planetary deities are like the astrological Avengers, each with their own special powers, attitudes, and horoscopic responsibilities.

You’ll usually find them hanging out together in a small shrine within the temple, all lined up like they’re posing for a very serious family portrait. And yes, Surya (the Sun) usually gets centre stage — because, well, he’s literally the star.

Navagraha (nine planets) shrine in a Hindu temple. Photo by Chainwit from Wikimedia commons licensed under CC by SA-4.0

Balipeetham (Sacrificial Altar)

Nestled between the Dwaja Sthambam and the sanctum like a sacred snack stop, the Balipeetham is where offerings (aka divine meals) are placed before being spiritually served to the deity.

Think of it as the temple’s holy buffet table — a place where food is offered, to honour them and keep cosmic balance in check.

It’s also the spot where you’ll find rituals happening with flowers, rice, lamps — all arranged with the care.

Balipeedam or the sacrificial altar in a Hindu temple. Photo by Pavuluri Satishbabu 123 from Wikimedia commons licensed under CC by SA-4.0

The temple tank

In South India, water tanks—often sourced from catchments or springs—are commonly associated with temples and serve the ritual purpose of ablution. Traditionally, Hindu pilgrims descend the steps to immerse themselves in a cleansing ritual, or at the very least, wash their hands and feet, and sprinkle a few drops of water on their heads as an act of purification. It is also customary to feed the fish with puffed rice, a symbolic gesture of charity extended even to the smallest forms of life. In recent times, however, due to the accumulation of waste around these sacred tanks, their perimeters are typically enclosed with chain-link fences—still allowing a view of the water while helping to protect the space.

Now that you’re armed with enough temple lingo to impress a priest (or at least not call everything a “gopuram”), it’s time to plunge into the real deal. Let’s explore these sacred spaces, one divine detail at a time in my other blogs about other temples. Shall we?

Why just read about it when you can live it? Come explore with me!"

With over two decades of experience in curating unforgettable journeys, we specialize in organizing tours across India, Southeast Asia, and select European destinations. Let us take you beyond the guidebooks and into the heart of each place we visit. Come travel with us—your adventure begins here.

Ask us:contact@wanderwise.me

Visit: wanderwise.me

Check: South India itinerary

Garbhagriha (Sanctum Sanctorum)

This where the deity resides in peace and quiet. “This is where the VIP lives, folks.”

The Dwaja Sthambham or the flag pole in a Hindu temple

Prakaram or Circumambulatory passage in a Hindu temple

Ablution and sacred tank of a Hindu temple