CALL/Whatsapp: +91 6304795901 or Email us at contact@wanderwise.me

MAHABALIPURAM - THE CRADLE OF SOUTH INDIA TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE

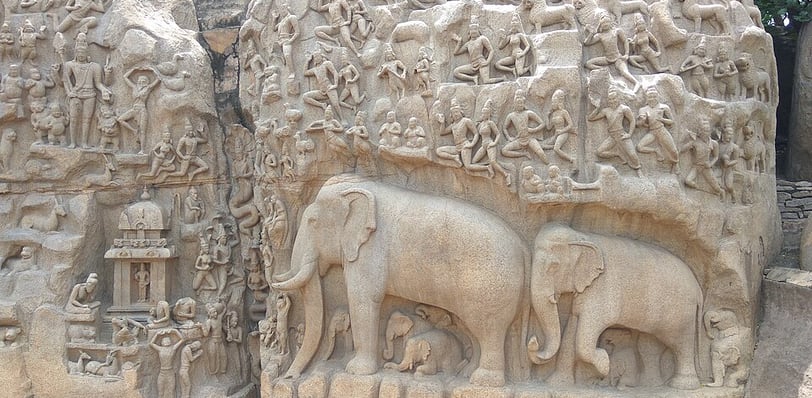

Mahabalipuram was once the bustling port city of the Pallavas, a dynasty known for its architectural ambition. It was here that the Pallava kings first experimented with granite—testing its potential for sculpting temples that could withstand time itself. What began as trial carvings on coastal rock soon evolved into an extraordinary legacy of stone architecture. The result: a breathtaking collection of rock-cut temples, cave sanctuaries, and sculpted wonders that now form a UNESCO World Heritage Site, standing as eternal proof of the Pallavas’ vision and ingenuity.

5/21/20256 min read

MAHABALIPURAM - STORIES ON STONE

INTRODUCTION

In the earliest phases of Hindu practice, there were no temples or idols. Worship was centred on the sacred fire (Agni), lit with sandalwood, twigs, and fragrant herbs. Offerings of ghee (clarified butter) were poured into the flames while Sanskrit hymns from the Vedas were chanted in deep reverence. The rising smoke was believed to carry the prayers and offerings to the gods and ancestral spirits, invoking their presence and blessings. It was a ritual of pure sound, fire, and intention, performed in open spaces—an expression of cosmic harmony rather than constructed sanctity.

The Vedic Ritual Tradition: Fire, Hymns, and Offerings: There were no temples, no murti (idols), and no permanent structures. Worship was ritualistic, not devotional—focused on sacrifices (yajña) and chants (mantras). Fire (Agni) was central. Agni, the fire god, was the primary medium through which offerings were sent to other deities.

Priesthood and Precision: Only Brahmins, trained in Vedic recitation and ritual, could perform these ceremonies. Rituals had to be done with precise pronunciation and timing (Siksha), often in open-air altars.

In the post-Vedic developments (~500 BCE onward) with the rise of Bhakti (devotion) and the Puranic deities (like Vishnu, Shiva, Devi), religion became more personal and visual. People wanted places to see and worship deities—thus temples with idols emerged.

In the mean time Buddhism popularized religious monuments and public art. From the 3rd century BCE onward, especially under Ashoka, Buddhism used Stupas (Buddhist temples), monasteries (viharas), and rock-cut chaityas to create sacred spaces accessible to the public. These structures were often visually appealing, symbolically rich, and widely visited. Stupas became spiritual centres that housed relics and attracted pilgrims.

Buddhism used art to teach and attract followers. Reliefs, sculptures, and murals on Stupas and cave walls (like Sanchi, Ajanta & Ellora) told stories from the Jataka tales and Buddha’s life. This made Buddhism visually engaging, narrative-driven, and attractive to people of all classes—not just elites or priests.

Now, the Hindus also wanted to be abreast of what was happening.

Hinduism responded and adapted. As Buddhism spread, Hindu communities began to feel the need for more structured spaces of worship, visible symbols, and accessible rituals. This likely motivated the gradual shift from fire altars to temples, especially as Bhakti (devotion) emerged. In fact, many early Hindu temples borrowed forms and styles from Buddhist models—especially in rock-cut architecture (e.g., Elephanta Caves, Ellora Cave 16 – the Kailasanatha Temple).

Temple building flourished during the Gupta period (4th–6th century CE) in North India. As the Guptas in North India began building structural Hindu temples in brick and stone, the idea of permanent sacred space spread south.

The Pallavas were deeply influenced by Buddhist and Jain rock-cut caves from western India (In places like Ajanta, Ellora, Bhaja & Karla) & Andhra Pradesh (Nagarjunakonda & Guntupalli). These sites featured chaityas, viharas, pillars, and intricate carvings—but were mostly Buddhist or Jain.

The Pallavas adapted the rock-cut medium to craft Hindu shrines of their own. Unlike the Guptas, who favoured brick and wood, the Pallavas daringly chose granite—transforming the region’s hardest stone into enduring sanctuaries of devotion and art.

The Pallavas’ choice of granite over brick and wood—used more commonly by the Guptas in North India—was both practical and symbolic, shaped by regional factors, political vision, and religious purpose. Although no direct inscriptions or texts explicitly state why the Pallavas chose granite over brick or wood, scholars generally conjecture that several factors may have influenced their preference for granite. The following are the possible reasons:

Local Availability of Granite: In the Pallava heartland (around Kanchipuram, Mahabalipuram, and Tiruchirappalli), granite was abundant, while good brick clay and timber were less so, or more perishable. It was natural to work with the hard stone available locally—even though it required greater skill and effort to carve.

Desire for Permanence and Immortality: Granite symbolized eternity. Pallava kings—especially Mahendravarman I and Narasimhavarman I—wanted their religious and political statements to outlive them. By carving shrines from solid rock (monoliths and cave temples), they demonstrated architectural daring, royal power & their devotion - cast in stone.

Technological and Artistic Ambition: The Pallavas had access to skilled sthapathis (temple architects) and artisans capable of granite carving, influenced by: Earlier Buddhist and Jain cave architecture, Rock-cut sites in the Deccan and Andhra Pradesh. Their experimentation gave rise to: Cave temples (e.g., Mandagapattu), Monolithic shrines (e.g., Pancha Rathas – the five chariots) & Structural temples in stone (e.g., Shore Temple)

Religious shift towards Agamic Worship: The rise of Agamic Shaivism and Vaishnavism demanded permanent sanctums and murtis (idols), which stone temples supported better than temporary brick or wooden structures. Granite temples allowed for complex iconography, sacred geometry, and the cosmic symbolism encoded in Agamic temple plans.

Thus was born the monuments at the grand UNESCO site of Mahabalipuram - the place of architectural experiments of granite stone. The story of Mahabalipuram, with its windswept shores and stone-carved marvels, deserves its own spotlight—and is being be told in the coming paragraphs.

FROM CARPENTERS TO SCULPTORS

In India, the master carpenters and craftsmen who worked on temples—often regarded as divine artisans—possessed an extraordinary command of the geometry and trigonometry of their time. Long before modern engineering tools, they applied complex mathematical principles with precision, ensuring everything from the temple’s orientation to the slope of a shikhara (spire) adhered to cosmic and structural harmony. Their knowledge was deeply rooted in tradition, yet remarkably advanced, enabling them to create sacred spaces that were not just architecturally sound but spiritually resonant.

Those master temple carpenters traditionally belonged to a specialized artisan caste known as the Vishwakarmas. Revered as descendants of the divine architect Vishwakarma, they were a guild-like community of builders, sculptors, carpenters, metalworkers, and goldsmiths. Within this group, the Sthapathis—temple architects and sculptors—held a particularly esteemed role. They not only designed and constructed temples with mathematical precision but also followed sacred texts like the Shilpa Shastra and Vastu Shastra, blending spiritual philosophy with technical mastery.

It is likely that these highly skilled Vishwakarma carpenters, traditionally adept with wood and sharp-edged tools, were summoned by the Pallava kings during Mahabalipuram’s early architectural experiments. Tasked with testing the sculptural possibilities of granite, their familiar woodworking tools were replaced with chisels suited for stone. Applying the same finesse, proportion, and design sensibilities they once used on timber, these artisans began carving granite as though it were wood. Through this transition, the carpenters gradually evolved into sculpting Sthapathis—master temple architects—laying the foundation for South India’s enduring rock-cut and monolithic temple tradition.

THE PLAN

Mahabalipuram is dotted with an extraordinary concentration of monuments—so many, in fact, that a single day isn’t quite enough to do justice to them all. That said, for the culturally curious traveller or the enthusiast of temple architecture, a well-guided tour covering just the three major monument clusters is more than sufficient to grasp the genesis of South Indian, particularly Dravidian, temple architecture. But first, a quick reality check.

The landscape of Mahabalipuram is strewn with granite rock formations that are the result of volcanic activity from over 3 billion years ago. These ancient rocks are notorious for their ability to absorb and radiate heat, making the area particularly hot. Combine that with the fact that Mahabalipuram sits right on the humid shores of the Bay of Bengal, and you’ll understand why most tour groups prefer to begin exploring early in the morning. It’s not a hard rule, but it’s certainly practical—to finish the site visits before noon and avoid the sweltering combination of sun and humidity. And the bonus? You’ll have more time later to relax and unwind in the many charming beachside resorts.

A Note on Exploring Mahabalipuram

When it comes to experiencing Mahabalipuram’s rich sculptural heritage, I personally recommend following a specific sequence that mirrors the historical and artistic evolution of this ancient port city. Begin with Krishna’s Butter Ball, then move to the Trimurti Cave, followed by the awe-inspiring Arjuna’s Penance relief panel, the intricately carved Five Rathas, and finally, conclude with the majestic Shore Temple.

This order isn’t just about sightseeing—it offers a chronological perspective on the Pallavas' growing mastery over stone. It allows visitors to see how early rock experimentation gradually transformed into architectural brilliance. While local guides or tour managers may prefer to reverse the sequence like a cinematic flashback, or even mix it up for logistical convenience, I believe that sticking to this natural timeline enriches the experience and helps connect the dots more meaningfully.

And of course, time permitting, you can elevate your Mahabalipuram experience by exploring some of its lesser-visited but fascinating monuments like the Ganesh Ratha, Varaha Mandapa, Old Lighthouse cluster, and the striking Tiger Cave, located a short drive north of the main heritage zone. For those who seek a deeper, more immersive connection with the town’s sculptural and spiritual legacy, consider dividing your visit into pre- and post-lunch sessions. This allows you to appreciate the details without feeling rushed, while also managing the heat and humidity of this coastal heritage site.

I won’t take you further on a verbally guided tour and spoil the joy of discovery by pre-empting every detail. Think of this as a gentle nudge—a way to whet your appetite for the wonders that await in this majestic UNESCO town. Let this be an invitation, not an itinerary. For more, visit wanderwise.me /drop a note at contact@wanderwise.me